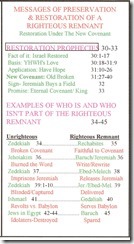

The major turning point of the book comes between chapter 29-30. Jeremiah now begins prophecies of restoration. This restoration will be based on God's commitment to the covenant he made with Israel at Sinai. God will now upgrade this covenant to a "new covenant." This "new covenant" is a prominent theme in the OT from Deuteronomy to the exile prophets. God will change the people internally so they will be fit for a new Exodus from all the places to which they have been exiled. In the NT, this covenant is viewed as inaugurated by Jesus at the Last Supper but not fulfilled until the eternal kingdom.

The fulfillment of the covenant promise is offered as the element of renewal. The ending of Yahweh’s work of judgment triggered a laying aside of anger (v. 24) that boded well for the scattered community of faith...In 30:1–31:1 past judgment at Yahweh’s hands is presented as a precursor to restoration. The God who punished the covenant people promises to reestablish them. Jeremiah 30, 340

New life in the land had its roots in a covenant relationship established long before...What guaranteed Israel’s homecoming was not simply Yahweh’s promise but also the theological continuity to which it bore witness. This continuity depends on the exodus or, more precisely, Yahweh’s self-revelation in the wilderness in a covenant-making role. Jeremiah 31.2-26, 345

Jeremiah 31:27–40 predicts the permanent restoration and blessing of Israel and Judah and their former capital and a transcendent realization of the covenant relationship. Subsequent history proved very different. The postexilic return to the land failed to live up to its promise. Yet it marks the inauguration of the biblical eschatological program. Jeremiah 31.27-40, 360

The last stages of the siege of Jerusalem, before it is destroyed in 586BC, is the historical background of 32-33.

Chapter 32 justifies Jeremiah’s seemingly bizarre symbolic action at such a historical moment. It was not a contradiction of his earlier messages of disaster, but a confirmation paradoxically based on them. God’s power to destroy was also available for renewal and restoration, which were guaranteed by Yahweh’s deep commitment to the covenant between God and people. Jeremiah 32, 371–372

Animals too would flourish again, and sheep are chosen as the example of such welcome normality, grazing in pastures and counted to ensure none had strayed...Such a panorama suitably concludes this litany of future blessings that is a celebratory medley of material from ch. 32 and reversals of divine judgments that appear earlier in the book. Jeremiah 33.12-13, 376

34-36 begin another section on the destruction of Jerusalem by showing the main reason: deliberate disobedience and disrespect to God's torah and covenant. This is illustrated by the actions of Zedekiah (34) and Jehoiakim (35-36). Zedekiah is given a promise that if he will give the Hebrew slaves their jubilee freedom the siege will let up. When he and the nobles do this, the Babylonians leave. However, when they leave, the leaders put the people back into slavery. Jeremiah then pronounces the return of soldiers and the destruction of the city. The rest of the section compares the obedience of the Rechabites to their ancestor, with the rejection of God's Word through the prophet Jeremiah. The argument is that if the Rechabites were faithful to their odd ancestor, "how much more" should the nation have been faithful to God and to his true prophets, who had been shown to be reliable.

In 34:1–22 the focus lies on flouting the divine torah as paving the way for certain doom. Jeremiah 34, 388

Whereas earlier the unit carefully contrasted the sect’s adherence to their human founder’s wishes with the people’s nonadherence to Yahweh’s will, admiring the principle of constancy rather than its content, the divine accolade guaranteeing the Rechabites’ survival is a climactic tour de force that condemns Judah by setting a higher premium on sectarianism than on nominalism. There was infinitely more hope for this fringe group than for mainstream Judah. Jeremiah 35, 393

One expects a reference to the burning of the scroll to appear in v. 29 as a reason for punishment, but it also spills over into vv. 27, 28, and 32 as a shocking deed that dominates the entire section. Indeed it should, because it corresponds to the crowning, unforgivable sin of rejecting the prophetic word in both Jeremiah’s poetry (6:16–19) and the prose sermons (e.g., 7:23–26). The narrator cannot help reverting to it again and again. Jeremiah 36, 399–400

Jeremiah 37-39 brings the story of the destruction of the temple and Jerusalem to an end with Jeremiah announcing the irreversibility of God's decision to destroy the city in 37 and the report of the destruction in 39. Zedekiah asks Jeremiah to pray for the city but Jeremiah announces that the city is doomed. The only way it won't be burned to the ground is if Zedekiah surrenders. He refuses and keeps Jeremiah in prison, even though he acknowledges that he is right. The officials response is to condemn Jeremiah to a slow, agonizing death by throwing him into a pit. Ebed-Melech rescues him (for which God rewards him with his life), but Jeremiah remains confined. Finally, Jeremiah, and those who really believed him, is vindicated as his word of destruction and death comes true as the Babylonians destroy the city.

Jeremiah’s continued imprisonment was tantamount to an indictment of a community that rejected the messenger along with his divine message. Yet the king’s response is at the same time meant to be read as an acknowledgment of sorts that the prophet was in the right, that in another’s words, “we indeed have been condemned justly, for we are getting what we deserve for our deeds, but this man has done nothing wrong” (Luke 23:41). Jeremiah 37, 408

A parallel is drawn between Jeremiah’s recent sinking into the mud (v. 6) and the prospect of Zedekiah’s feet sinking into metaphorical mire. The two crises are linked as cause and effect. The rejection of the prophetic message that resulted in Jeremiah’s dire predicament, despite the partial amelioration granted by the king, was to land Zedekiah himself in a comparable predicament. Jeremiah 38.21-23, 415

Their treatment of God’s spokesperson is thereby shown up as justifiably inviting the tragedy duly experienced by the king, the city, and the people whom the king and his officials represented...it spells vindication for Yahweh’s message and messenger. Jeremiah 39, 418

Chapters 40-43 tell the story of the survivors of the destruction of Jerusalem. Jeremiah joins the group under the new Babylon appointed governor Gedaliah. Jeremiah continues his message of submission to the Babylonians so that they will live and prosper in the land. However, his message is rejected by the military leaders and Gedaliah is assassinated. The Jewish leaders come to Jeremiah asking for guidance from YHWH, but Jeremiah recognizes that their minds are already made up to go to Egypt. When Jeremiah gives his oracle that if they stay in the land of Judah they will be blessed, but they will encounter the Babylonians they fear if they go to Egypt, they refuse to listen. Even though God gave them graphic signs they would not put their faith in him. Decisions made based on fear of circumstances, rather than trust in God's promises almost always lead to disaster.

(The) nondeported Judeans would be faced with a great opportunity to settle in the land, which, however, they ultimately failed to take...Jeremiah is presented as throwing in his lot with a new community of hope—hope that later would be tragically dashed. But his choice represents a validation of that community. Jeremiah 40, 431

It is all summed up (v. 18) as a terrible divine intervention that in intensity would match the disaster that overwhelmed Jerusalem in 587. The door is slammed on a potential scenario based on ch. 27 of continuing life in the land and also on an Egyptian diaspora. So “the future of Israel lay with the Babylonian diaspora.”...The promise of building and planting lay elsewhere, not with the Egypt-bound refugees. Jeremiah 42.13-18, 437–438

Chapters 44-45 end this section and look forward to the prophecies against the nations in 46-51. The people in Egypt argue with Jeremiah and propose a different reason for the destruction of Jerusalem. They say that the reason for it was that they failed to worship other gods like the "queen of heaven." Basically they were citing Josiah's revival as the reason for their loss. Jeremiah tells them that they will be proven wrong and they will become wanderers throughout the world. The section ends with a older prophecy about Baruch, that promises preservation and peace to the faithful wanderers of the Jewish diaspora. God gave the people every chance to remain in the land and be blessed. They chose to go to Egypt, but it would be the returned exiles from Babylon that would carry on God's plan.

The Judean Diaspora in Egypt seems to have continued, despite setbacks; in due course the LXX, produced by later immigrants from Judah, became a tribute to its importance and influence...The real destiny of the Judeans lay with the Babylonian Diaspora, whose return was to trigger the ongoing development of mainstream Judaism under the providence of God for centuries to come. Jeremiah 44, 449

Presumably the prophet himself, now aged, was soon to die a natural death in Egypt, but in his stead his younger ally was promised life and independence. Although he now found himself among the accursed refugees in Egypt, he was to be one of the survivors (44:14, 28); the promise there finds illustration here. “In all the places” seems to have a Diaspora flavor (cf. 8:3; 24:9; 29:14; MT 40:12), warning that Judah’s redemption awaited a later time. Baruch “was a type of the one on whom promise rests.” Jeremiah 45, 453

No comments:

Post a Comment